On the 1st of January 2021, continental trade between African countries significantly changed with the official commencement of the African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement (AfCFTA).

The AfCTA was an initiative that had been in the pipeline since 2012, with five years of negotiations and other logistic planning, which finally crystallised on March 21, 2018, after 44 African countries signed the pact at an AU extraordinary summit in Kigali, Rwanda. Shortly after, 10 more countries, including Nigeria, added their signatures, and the operational phase of the AfCFTA was marked to kick off by mid-2020. However, the covid-19 pandemic threw a cog in these projections, leading to a delay in starting operations until 1 January 2021, when the AfCFTA officially kicked off.

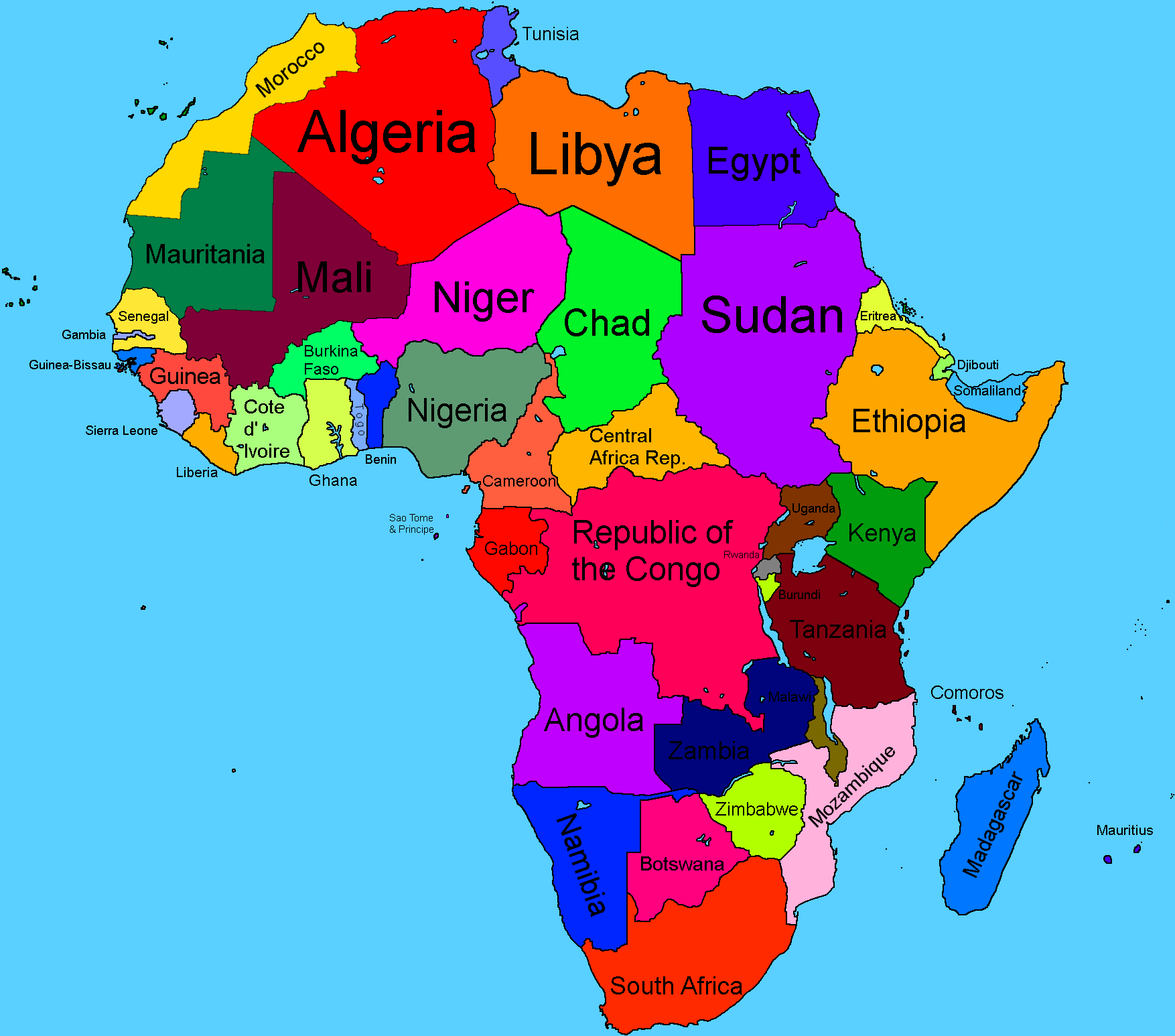

African countries have not been able to scale up their economic activities due to a variety of reasons exacerbated by the conflicts in the 7 different regional trading blocs currently in operation, hence the need for a deeply integrated and outwardly united front from which to achieve the cohesion needed to boost the scale of economic activity in Africa. This considered, the AfCFTA is aimed at creating the world’s largest free trade area; one that integrates 1.3 billion people across 54 countries.

As at December 2021, 41 out of 54 signatory countries have ratified the treaty, making the AfCFTA the fastest instrument in the African Union to be ratified. The ratification is significant as it signals the increasing interest of the State parties. The fact that the top 4 economic powers and richest countries on the continent, Nigeria, South Africa, Egypt, Algeria have ratified the trade agreement is clearly also significant.

The year 2021 also saw the roll-out of the pilot phase of the Pan-African Settlement System (PAPSS), a combined initiative of African Export-Import Bank (AFREXIM) and the AfCFTA, which was formerly launched in Ghana on 13 Jan 2022. The PAPSS serves as the continent-wide platform for the processing, clearing and settling of intra-African trades and commerce payments. The system was developed by the AFREXIM and promises to reduce the cost and time of payments, lower the level of banking liquidity required to make payments, and improve central bank oversight of payments.

The full implementation of PAPSS is expected to save the continent more than US$5 Billion in payment transaction costs each year.

Given the interests generated by the AfCFTA and the potentials it holds for established businesses, start-ups and SMEs, it is expected that 2022 will provide another opportunity for the State Parties to make significant progress.

According to the UN Conference on Trade and Development – UNCTAD’s Economic Development in Africa Report 2021, the total untapped export potential of intra-African trade is around $21.9 billion, equivalent to 43 per cent of intra-African exports (yearly average for 2015–2019), with an additional $9.2 billion projected through partial tariff liberalization under the AfCFTA over the next five years. This statistic highlights the ultra-low level of intra-African trade when compared with that of countries in other continents, and in particular reflects Africa’s unenviable position as an exporter of raw materials to the rest of the world.

Optimism v Action

After the optimism that greeted the official launch of the AfCTA, one year after the launch, trade restrictions between African countries still abound. Although the pandemic may have had some effect on the AfCFTA’s integration goals, the reluctance of African leaders to open up borders and liberalising trade remains a major impediment.

AfCFTA had projected that the phase II negotiations consisting of the underlisted would be finalised and ratified by the end of 2021, namely:

- Trade in goods and services,

- Intellectual property rights

- Investment and competition policy, and

- E-commerce

The AfCFTA projections above have not been fulfilled and there are still many loopholes in negotiations that were not finalised in 2021 among member countries. There is still a feeling of uncertainty concerning where countries stand on the agreement— an uncertainty that has affected the AfCFTA’s implementation.

The abovementioned phase II negotiations and the general framework for trade in services appears to have taken a back seat pending the conclusion of the negotiations on rules of origin.

The following are the three key challenges:

- With African countries favouring protectionist policies in their African trade outlook, there is some unwillingness by State parties to ratify all the articles of the agreement exemplified by the prolonged negotiations on phase I consisting of rules of origin. Many African countries are still holding out on ratifying some of the phases of the AfCFTA. These countries, who make most of their revenue from exports to non-African countries, are yet to be convinced of the benefits that the AfCFTA to their economies.

- A lack of a manual of information for African businesses about the AfCTA regarding the ways to take advantage of it, and a substantial percentage of African businesses are still unaware of its terms (particularly the tariff arrangements). Until businesses are aware, the costs of trading under AfCFTA will remain high.

- A lack of customs infrastructure and policy to be able to complement the AfCFTA’s customs and tariff obligations (only three countries in the AfCFTA so far have the infrastructural and systemic customs capabilities on par with AfCFTA benchmarks), as well as a lack of capacity in the AfCFTA’s Secretariat to push the integration agenda, given its launch in the middle of the pandemic.

Private Sector Initiatives

Reports suggest that the AfCFTA enjoys wide acceptance and heightened interest amongst the young African entrepreneurs and SMEs who are ready to explore the potentials that a larger African market presents.

Private sector start-ups have notwithstanding the delays of States parties sought to integrate African trade with start-ups offering services for company formation and compliance across Africa’s 54 countries and others offering a single digital infrastructure for businesses to start, scale and operate in every African country efficiently.

More traditional companies namely, two of Africa’s major logistics companies, Ethiopian Airlines Group and A-E Trade Group, signed a MoU to establish the East African smart logistics and fulfilment hub, committed to the establishment of a business relationship to provide end-to-end logistics solutions across Africa. Also, some AfCFTA-focused organisations like the AfCFTA Young Entrepreneurs Foundation (AfYEF) – have been formed. This and many other intra-African private partnerships and agreements show that the private sector has been more enthusiastic about the AfCFTA than African governments so far.

Expectations in 2022

The priorities for the implementation of the AfCFTA regime is for the finalisation of negotiations such that the following are agreed upon:

- Member States should ensure the attainment of at least 90% attainment of the Rules of Origin. The Rules if properly crafted remain the building blocks for the industrialization of Africa through increase in local production and cross-border value chains. There are over 6000 tariff lines under the HS Code system and the AfCFTA ambition is to liberalize over 90% of them. The AfCFTA Rules of Origin would require that only made in Africa goods will benefit from the tariff concession. However, measures must be put in place to prevent its abuse as non-compliance will turn the member countries into dumping grounds and lead to significant job losses and displacements of workers in key sectors such as agriculture and manufacturing.

- Addressing non-tariff barriers in order to harmonised customs interconnectivity system and transit procedures across the major trade corridors in Africa. For example, the Abidjan to Lagos trade route/corridor deserves special attention in view of its significance to the ECOWAS region. The non-tariff barriers inhibiting intra-trades across the Regional Economic Communities (RECs) should also be addressed.

- Providing access to private businesses and individuals of general information about AfCTA particularly about progress in Phases 1 & 2 negotiations.